Simon Wheatley: “Grime will never be dead”

- Tahlia Lorenz

- Jan 8, 2021

- 3 min read

Updated: Apr 9

(Cover image courtesy of @mh_photos_london)

This week, I caught up with famed documentary filmmaker and photographer Simon Wheatley (@simonwheatleyphoto) to discuss the awakening of grime through his lens and his professional journey.

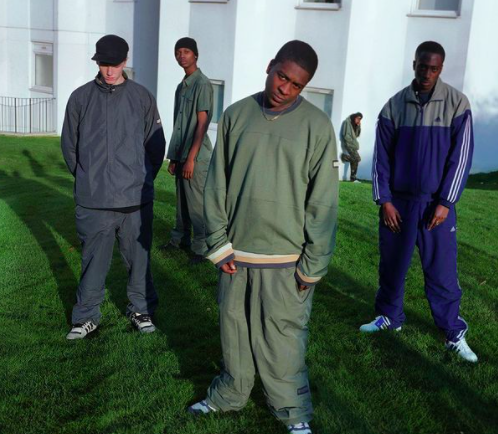

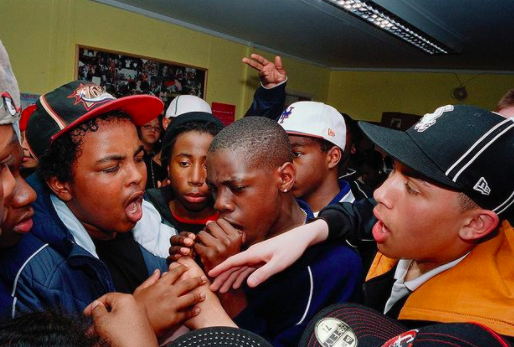

Throughout his career, Simon has produced some remarkable work, including his prodigious publication Don’t Call Me Urban: The Time of Grime (2010), a collection of photographic moments spanning twelve years, which organically captures London’s youth culture during the formative years of grime.

When reaching out to Simon, he shared:

“I’ve met a few people over the years, yes. Though, I was always interested in the lesser known folk, those who constituted the fabric of grime itself.”

While his focal point was never on capturing specific artists but rather the expressive essence behind the movement, Simon has snapped a multitude of individuals who have since become grime royalty, including Skepta, Giggs, Wiley, and Kano, to name a few.

(Images courtesy of @simonwheatley)

What sparked your interest in photographing and documenting grime artists?

I was never really interested in photographing any artists. I’d see people like Wiley and Tinchy around at parties or on the block, but I’d never feel I had to get a picture of them. I was more interested in grime as a social reflection.

The youngers I used to roll around the youth clubs with, and to late night radio sessions, were far more interesting in that they were really living what grime was about. I was fascinated by the harshness of the expression; the social alienation that I could feel.

What do you believe was a pivotal point for grime?

I think both in retrospect and from what I could sense at the time, Boy in da Corner was a pivotal moment when it won the Mercury Prize. grime became something.

How does the industry today compare to its early days? What stands out most?

Obviously, the audience has shifted. Back in the day, it was basically ‘the ends’ with the odd person who was in the know. By the time I began my documentary film about The Square, the standout crew of the second generation, the audience was basically white — certainly at the front.

It’s good grime found a wider audience. Though, I have often been at events and felt a fundamental disconnect, which I didn’t feel back in the day when I was, say, in someone’s room in a bow tower block listening to a late-night set.

I don’t feel the new audience appreciate the social dimensions of the genre, the pain and struggle from where it emerged. And the way brands have rather colonised grime is also part of the same phenomenon.

Do you think the political element of grime has lost momentum over the years?

Even from the very beginning, grime was not a political statement in a direct sense — in the way original hip-hop was. Indirectly it was of course very political. The expression of that raw energy, that frustration, angst, alienation, anger, all those pent up feelings that would explode in the youth clubs when someone got the mic.

Grime was the voice of post-Thatcherism, of community breakdown. Very political!

But, consciousness was never prominent, and the search for mainstream recognition — and the financial rewards that encapsulated it — were always part of the scene.

What is your perspective on the ‘grime is dead’ debate?

Didn’t Logan Sama have a ‘Grime is Dead’ T-shirt a decade ago or more now? Grime will never be dead, even if other genres from the same demographic emerge.

Reflecting upon your career so far, what projects have you most enjoyed working on and why?

Hard to say. I’ve enjoyed Don’t Call Me Urban, which continues in a really enjoyable way because I feel so much love from people who’ve grown up with my pictures.

When my daughter was born in northeast India I photographed the small town of her birth, near the India-China border.

It was a time of great joy for me and the pictures reflected that, and also my fear at the world I’d brought a girl into. I enjoyed it because I adopted the principles I’d absorbed from Taoism into my photography, flowing like water, resisting confrontation, seeking the path of least resistance, as I sought the light.

What’s next for you? Are you working on anything at the moment?

I’m working on so many things — where do I start?

I’m also afraid to talk about them because I’ve learned that’s a good way for them not to happen! I have so many projects I’m drowning in them.

Listen, about twenty [years ago], a friend of mine in Amsterdam, where I was living, said that I was trying to do too many things. He said just focus on photography for a bit and see where it takes you. It’s like I’m back there again, in a way, just trying to do so many things!

Commenti